Installing Linux software applications

Introduction

There are many ways to get new software installed on your Linux machine, and I will outline a few below. I'm mainly using Ubuntu nowadays, so most of the explanations are made from this perspective, though I'd expect most of my comments will apply to Debian based distributions and will outline a way to approach things for others.

First of all, an application must be at its core a file in a format that your operating system understands. Also, in order to simplify software development, people came up with the idea of reusable code, so that you don't start from scratch with every tool/application that one wants to create. One simple example would be if someone wanted to build an editor, they should not have to write the code for building GUIs or the operating system kernel. All of this lead to the emergence of software libraries which at the end of the day are some files we put on our disk.

So, many of applications we use day to day are broken up in multiple files, including configuration one. So, it is no wonder that there are widely available and popular solutions that try to package applications in a standardized way (usually an archive that respects some predefined directory layout).

You are probably already familiar with one of the below:

- .deb

- Debian based distributions

- .rpm

- rpm based, such as RedHat and OpenSUSE

- .dmg/.img

- macOS

- .msi

- Microsoft Windows

As outlined above, there are common frameworks/libraries that are needed. Obviously you could potentially package them with each application, but the size of them is sometimes too much. For instance, if you were to depend on most of the GNOME libraries, you'd have to package 500MB-1GB every time (this was estimated based on how flatpak and snap package GNOME, don't worry I will explain what they are later on).

george@local:~$ snap info gnome-42-2204 | grep installed This snap is automatically installed and removed when needed. **Manually installed: 0+git.510a601 (176) 529MB - george@local:~$ flatpak info org.gnome.Platform/x86_64/47 | grep Installed Installed: 1.0 GB

As a side note, it's not only disk that is saved, but RAM as well, as operating know how to load the shared libraries in memory once for multiple applications.

Therefore, the idea of dependencies between packages came along, so you'd be able to have a single copy of all those binaries.

Unfortunately, there's one more important aspect to this. These libraries have new releases (which might change behavior intentionally), and also there might bugs related to the interaction between the application and its dependencies, which basically means an application is compatible with certain versions of libraries

In order for its users to have a smooth experience, a distribution needs to test and pick the right combination of all these applications and libraries, package it together in a ISO image, which you can then put on a USB flash drive. There are periodic releases and this would be one way to get newer software.

As the Internet has become widely available, the package managers have evolved and are offering online repositories as well, which make the (security) updates much easier.

When you install an application, there a few things to consider:

- Trust

- does what you want and is not malware

- Interaction with your OS

- works well with infrastructure/other applications

- Easy to uninstall

- easily remove its files/data to avoid polluting your disk

- Easy to manage

- common way to configure/install/uninstall, so that you don't need to learn a lot of specifics for each application

- Space on disk

- how much space the end installation will occupy on your system

- Performance

- how is the application responsiveness impacted by the installation approach

Given my criteria above (you may or not agree with them), the preferred way of installing something from my perspective is a package manager.

Here's my prioritized approach on getting new stuff on my computer:

- Default distribution package manager (APT for Debian based distributions)

- Distribution agnostic package managers (flatpak, snap, Nix, npm, etc)

- Manual installation

Of course, I install the majority of the games I play via Steam which is yet another package manager.

Also, if you find that most of the apps you need are shipped with the distribution, but have an older version, you should look out for new releases.

Default distribution package manager

Using the provided solution from your distribution is a no-brainer for me, as it tries to make sure everything is curated and works well together. Most of them provide both an GUI/CLI management application.

The details below apply to Debian based distribution (that means APT as a package manager), but you should probably be able to find similar functionality on other distributions (see a CLI functionality comparison for multiple package managers here.

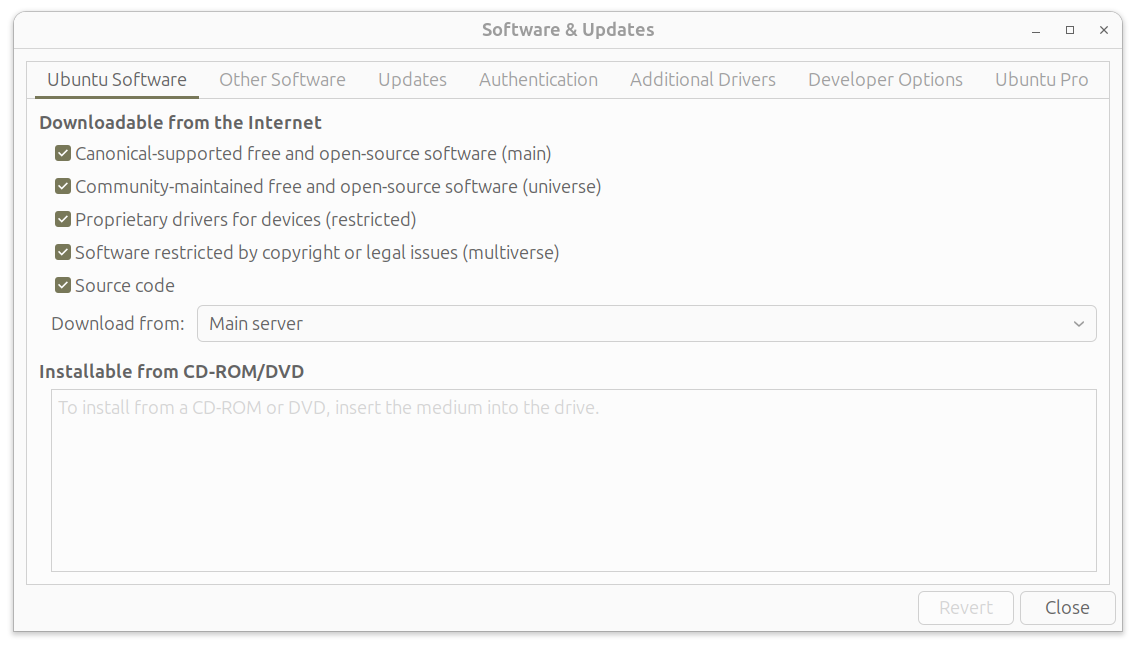

Firstly, for best performance you should go ahead and configure a mirror if not already.

If you're using the GUI, I recommend the "Software & Updates" app (see "Download from" below):

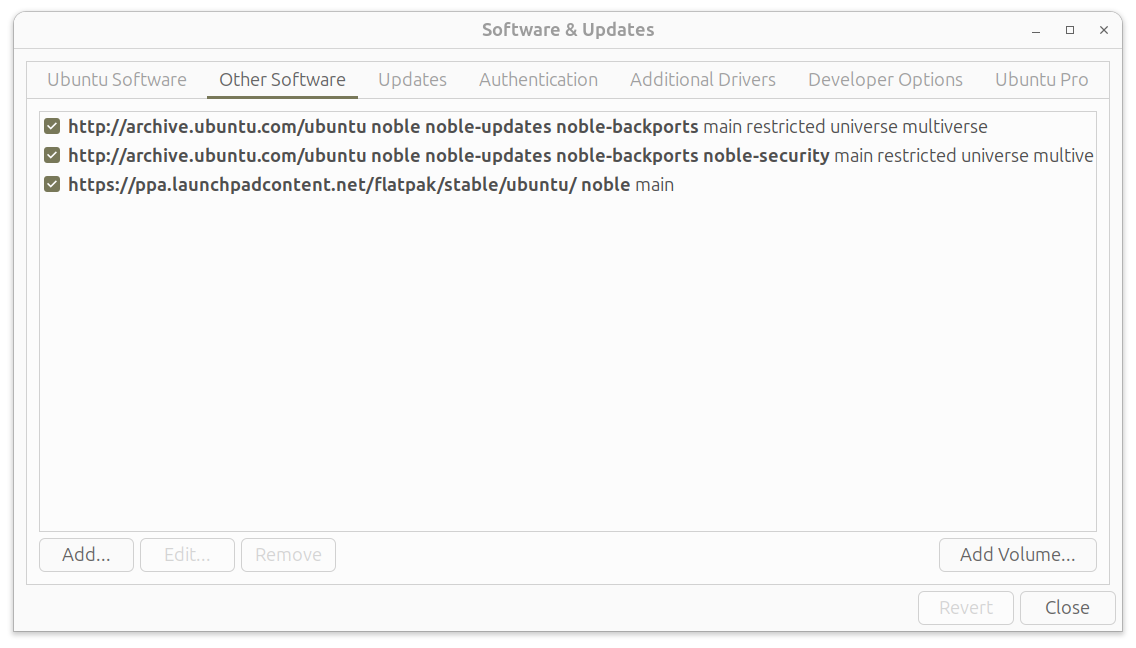

Some applications are not in the main repository, but might be found in others. Ubuntu offers some centralized place for them via their Launchpad infrastructure. It is also used for Canonical internal testing, but it has been extended since to allow third party publishing as a Personal Package Archives(ppa).

It's easy to search ppas, but it's hard to reason as to what is recommended for use or in a good state. I don't usually resort to ppas, as it's easy for them to put your package manager in an inconsistent state (because of not enough testing, incorrect dependencies, lack of updates). I only consider using them when the application itself recommends it and I know it is popular enough to be kept up to date.

As a side note, Debian maintains another solution called extrepo, which seems to be available on Ubuntu as well. It has a curated list of external APT repositories, but I have not tested it though, so I wouldn't be able to recommend it.

I have decided to add the flatpak repository. Trust is always an issue, so please be careful what you add.

It is a bit harder to get a full picture from the GUI, so going deeper into the configuration files/CLI is my preferred approach.

See below on how to get a unified list of repositories via apt-add-repository. Please note the special security repository, which helps keeping your system secure.

Repositories are saved in the file /etc/apt/sources.list (Debian approach) or stored as individual files in /etc/apt/sources.list.d directory (Ubuntu 24.04 approach).

george@local:/etc/apt/sources.list.d$ sudo add-apt-repository --list [sudo] password for george: Types: deb URIs: http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu Suites: noble noble-updates noble-backports Components: main restricted universe multiverse Signed-By: /usr/share/keyrings/ubuntu-archive-keyring.gpg Types: deb URIs: http://security.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/ Suites: noble-security Components: main restricted universe multiverse Signed-By: /usr/share/keyrings/ubuntu-archive-keyring.gpg Types: deb URIs: https://ppa.launchpadcontent.net/flatpak/stable/ubuntu/ Suites: noble Components: main Signed-By: -----BEGIN PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK----- . mQINBGERGM0BEAC+3QHbpl2ZAnJxoiNXqAc/CkkAQwUc1rvJLqxUVctIWPw5+zVt mJEpmAEfiz+t/EaBrmNUMi+8fKkjRCiaFeKpaOHGA/WALxuEbVFR/YtA48IhdK1S +YPueMsVDJdwG+TvG+8c/C5nJWjDwUDQVYqRRuXsd+256jN45F4Xs1y3eHX3blS9 yOHpkOTlOhZYe7dN/+PUEz8HXfqfQBjlnpdDAV9DP4bgZnHzwbdN0L59nJitCS2N FrxpTYtF/Mv9PeZc5F8e62Ck5mGtfTWPgusoIw/0aGbVXoOUoZY+uX1b8lUI4rj/ cw5PndCEX1LsUAsmpzt5iZdXaxLCt/NUfbI1nki+1WyquZPCScQqhXohCf9D8Uxu h1TTmJ+jRJbfyoNMnlcGkIz+3g1V9wD1w4+wRCZLSnToa0XYrDJkXVPtIYsmgelE /mQeCHFpsQEFxa94bkRhRb1C/CAKrQ5yMtREnP8l/0yyYkOHCFh41nC+sN1oxX89 T0cpX2hnB8cs4AUbonz80UkMk6zeQwUg1yHgdX7gLoELnZVwctA03nB9SJW6BPG/ kgMrReHKn5diZWz0RhDTz0K0qh4NUdcKtK4oJZ7Lk5OGSR6N0f/zIBKVCNo9jzK3 E8zFeMzWelXlUEQ5k9GsxF9XThVJ0On2RHMRjUUQbRVR4HjoyI77mk5kXwARAQAB tBlMYXVuY2hwYWQgUFBBIGZvciBGbGF0cGFriQJOBBMBCgA4FiEEXG0VOhfALDN+ 9sZjuLnUEinfpfUFAmERGM0CGwMFCwkIBwIGFQoJCAsCBBYCAwECHgECF4AACgkQ uLnUEinfpfXYUw//Yfl7rRaZ/tbLjtOMUHlcQoQdrZ0FkaubNGz8ydyBe37Xulij Ss6zAamdEqERZ9VuAiKhwc7oEfRqigaZpXvzMcO2fdg7nF4S3yRckUcShAkoO8IO i33paHWxo03tU6FpncAJeuWXhsFl8FOhD1dkoOG2rqELaMd2TKOF7+OuGA6Y4DvH eHPOhXqhn65vVzuUGQTXce6tsZfRHNYvMkAdRAqCo731ZlY8ilSHW9hwGYnFsRZ5 +n4E6ZPCOtWAbapa+iCmV/liRLB+VZ+MP3tUaFHk/yeCllCjsmxmNAIA31hTOXTQ aAt7t/wjZMWC/x1S6kJKvq/to2vyHPtlCAH7Y8HBumQ2NXfCgt2yk/2TyvpmxEUh +9/XRw3VoSXK3lL1muK3af1o6VSoFiUNyrIJSO8UhE/Dz6ykcSJfOqM7G/9Mlosw FaAgHDBd9rb8lUz3RIu7n3t292UuuuPmQd5kby4/SPvc4lHdQHD415fFOcF2nzZG 786a6cqu8+1MpUPcg1HVNe3fz3kliIrnYfDHk5ic3D2wS9iGn5brDJYwcqsCYpF/ 66XSJB6vXNGamOdQ1GKKUEh0ilfVEvmX+a+ovo4G4YQ16iHQO0JzC7SVe/+ITSNY o5RT+82ocwyNGzBPzKmRqKV99baRT63dD9NVs0u0BjihRyMWCUwfWYwNtlI= =Fi60 -----END PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----

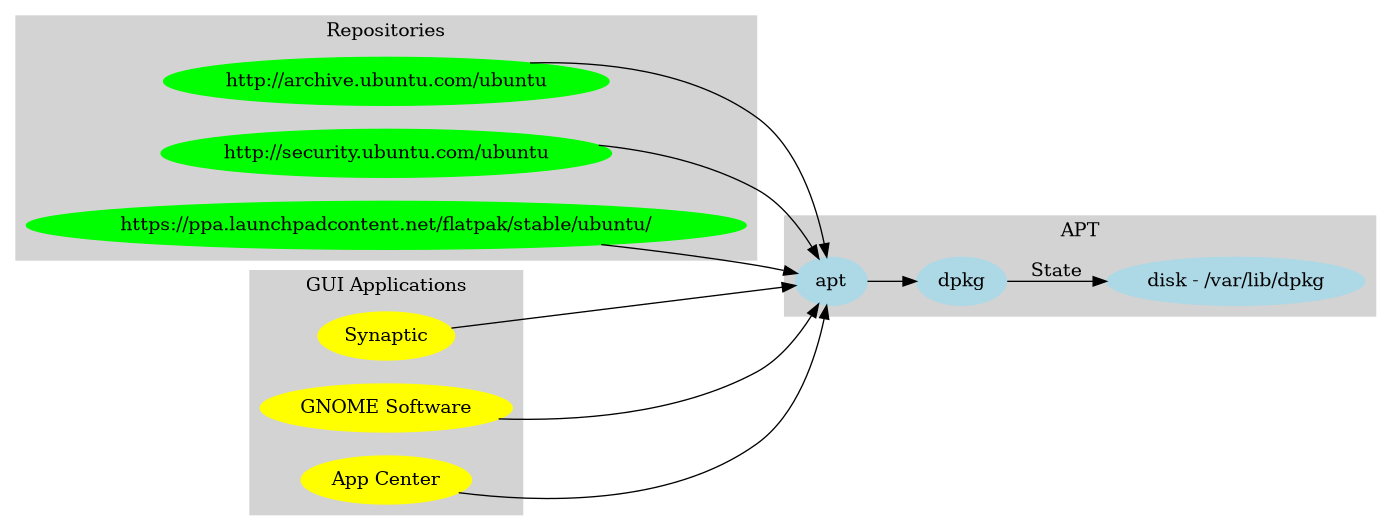

I've outlined below a high level overview for the package management infrastructure. apt is the high level package manager, and is responsible for resolving and downloading dependencies. It will then defer to dpkg low level infrastructure to install them.

Distribution agnostic package manager

As you may have already figured out, many Linux distributions have different package managers (see below). It is therefore a lot of work to have a global presence.

You can also check out for instance the Firefox distribution plan to get an idea of what one may need to cover. So, it is unfortunate, but understandable, that application developers seek out distribution methods that are cross-platform.

In theory, it is possible to install one of the known package managers associated with distributions (e.g. you could install pacman on Ubuntu). However, given that the package manager is such an integral part of the overall experience, this is not a common thing among the Linux users.

Once an external package manager accepts that you can potentially deviate from the distribution provided libraries, it has to find a way to isolate its binaries and bootstrap itself.

So, please keep in mind though that an extra package manager comes with an additional learning curve, extra bootstrap disk space and potentially more RAM being used. This is why it's important to keep the extra apps installed outside the native package manager to a minimum.

There are two main contenders out there, specially built for Linux:

- flatpak

- community driven, main app store available at https://flathub.org/, other stores supported

- snap

- a Canonical initiative, app store available at https://snapcraft.io/

Here's a quick cheat sheet on how to achieve the simplest things when using the CLI tools offered.

| Package Manager/Command | Debian APT | Snap | Flatpak |

| Update repository(s) package list | apt update | Combined with update (snap refresh) | Combined with update (flatpak update) |

| Find package | apt search package | snap find package | flatpak search package |

| Install package | apt install package | snap install package | flatpak install package-id |

| Update package | apt upgrade | snap refresh | flatpak update |

| Run app from package | app | snap run app | flatpak run package-id |

| Uninstall package | apt remove package | snap remove package | flatpak uninstall package-id |

Flatpak

Flatpak was a community effort that started initially in the GNOME community and has expanded to a level where it recommends it for software distribution. It has excellent documentation as well, you can find the steps for installing on Ubuntu here. It is geared towards desktop applications and therefore offers GNOME/KDE runtime environments. Its main online repository is flathub.org, which offers some basic verification features, as well as installation statistics to help understand the relative popularity of various apps. It isolates the binaries via sandboxing approach, more specifically, using bubblewrap. You control the permissions via Flatseal.

The main GUI application is GNOME Software, which supports it via plug-ins. Also, you can use the flatpak CLI executable

george@local:~$ dpkg -l | grep flatpak ii bubblewrap 0.10.0-1~flatpak1~24.04.1 amd64 utility for unprivileged chroot and namespace manipulation ii flatpak 1.14.10-1~flatpak1~24.04.1 amd64 Application deployment framework for desktop apps ii gnome-software-plugin-flatpak 46.0-1ubuntu2 amd64 Flatpak support for GNOME Software ii libflatpak0:amd64 1.14.10-1~flatpak1~24.04.1 amd64 Application deployment framework for desktop apps (library)

Snap

Although mainly driven the Canonical (the company behind Ubuntu), it can be installed on other Linux distributions as well (see details here). Although many parts of it are open source, it has not picked up as much in the community, probably because it doesn't allow any other online repository aside from the one from Canonical. Its main advantage in my opinion is that it provides support for CLI applications as well. Separately, there is some notable slowness compared to native packages, usually in the application startup (See the Firefox series).

The main GUI application is App Center, but one can also use GNOME Software that supports it via plug-ins. Also, you can use the [[https://snapcraft.io/]snap CLI executable, which should be there by default in Ubuntu.

Other package managers

Aside from this, for CLI apps, I'm also using Nix and, somewhat unexpectedly npm (some apps may be shipped with it even though it may not necessarily be linked to the node ecosystem). I usually need from them packages that are used for application development, so I'd say they are not something an average user would need to delve into.

Manual installation

All the applications provided to the end user rely on some build infrastructure. You can, of course, also install it on your system and recreate the binaries. You can then control where they go on your system, and you'll basically have to manage it yourself

Some people have created AppImage, a file format that contains the full application and its dependencies. With this approach, you get to skip the building part, but need to handle everything else. Its philosophy seems to not rely on a package manager at all, although I've seen utilities from people trying to offer this as well. There is a popular central repository that aggregates a lot of them (1.4k as of today). The idea is interesting, it would probably be OK to have a few apps like this, but I wouldn't go further than this.

If I need to get the manual route for an app, I usually go and check its website, and usually take their recommended approach.

Closing thoughts

Although Linux is considered to be very safe, the same threats apply. You need to be cautious and do a basic analysis of the software you're installing, as well as its source.

Each Linux distribution has a good story for the security aspect, see the Ubuntu story or the Debian one. Also, installing via the distribution package manager ensures that there's some minimum testing that has been done for proper interaction with all the other apps/components, as well as some basic identity validation.

For new applications, you should always be looking at least at the publisher, especially if you use the alternate solutions (in order to relate it to a trustworthy source).

See the GNOME Text Editor links below to get an idea of where to look:

- snap

- https://snapcraft.io/gnome-text-editor

- flatpak

- https://flathub.org/apps/org.gnome.TextEditor

- apt

- https://packages.ubuntu.com/noble/gnome-text-editor

Installing Linux software applications is straightforward, pretty much on par with other operating systems. Upgrading your release regularly is also a good practice.